Allrighty, today we talk about . . . panel mapping.

Any house that has electricity has a panel full of circuit breakers, and it is oh so very very helpful if those circuit breakers are labeled. Sadly, all too often, panels are installed with no labels, so it falls to someone else to label them down the road.

The reason they need to be labeled is, well, ok, any competent electrician can usually trace a circuit and identify and kill the breaker. The issue is, what if it’s an emergency? In that case, you have to kill ALL of the power with the main shutoff, and now you may not have any lights.

It’s just a good thing to have them all labeled in case a service guy comes to fix the dishwasher, that way he hopefully won’t charge you extra for the time taken to find the breaker before fixing anything.

Also another note, Belmont and Brookline (local towns here) are now requiring all city-permit-issued electrical work to include mapping/ labeling the panel.

Now in my case here today, one of my regular clients has a big (and I do mean big) old Victorian house, and lately I have been having to go over there at all hours to fix heating issues. AND . . . the panel is not labeled, so when I am over there at 2 am trying to shut off power to a burst hot water heater, the lack of any labeling has been getting to be a bit of an annoyance. So I finally talked him into letting me do some panel mapping,

Now for all you intolerant electricians out there, please bear in mind, I have been working with a master electrician for 7 years now and I am a de facto trainee and I already know a lot but even then, I only do basic stuff like the occasional switch swap unless he is standing there supervising. As he was here.

Okay, to illustrate, here is the panel in my own apartment.

Nice, concise, clean, altho I think it could have been done better. It’s a nice list but one must first locate the name of the appliance or circuit on the top left list, then look at the chart below it to see how the breakers are numbered / laid out, and then go to the breakers themselves and count up from the bottom to find it. Wouldn’t it be so much better to just have the appliance name right on or next to the breaker?? This is the kind of thing I am trying to make better.

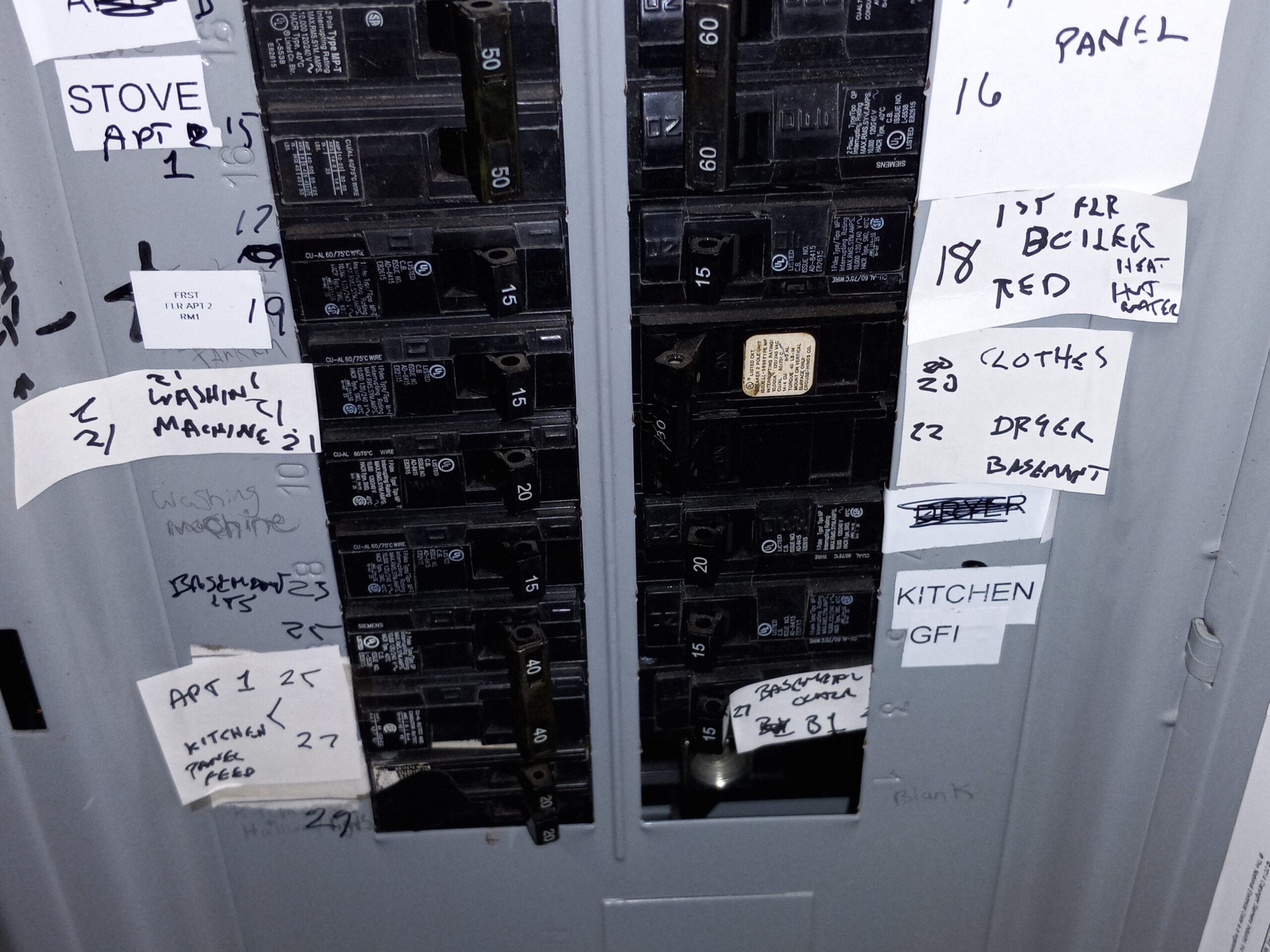

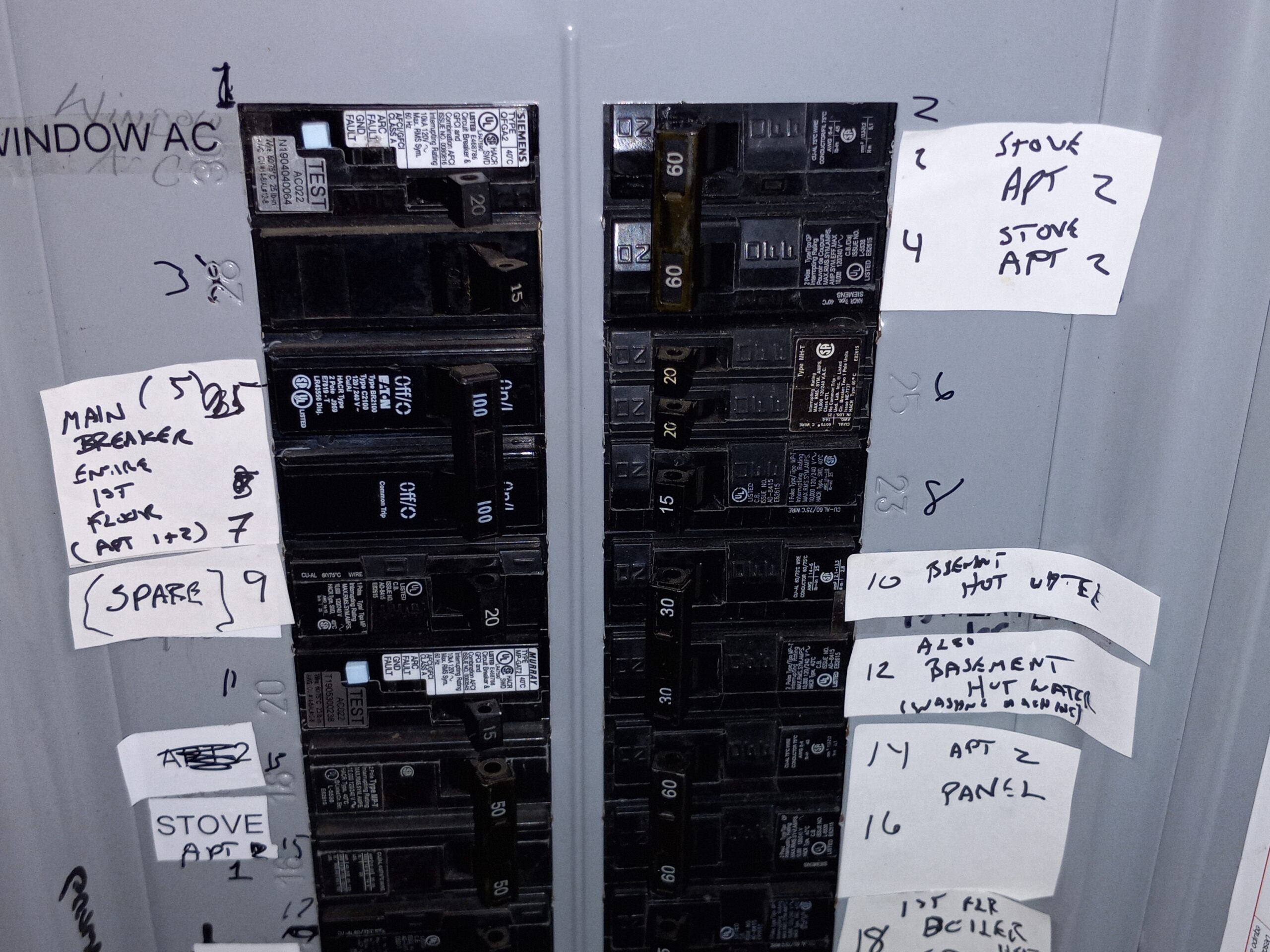

Here is the “before’ shot of the old house panel.

Someone had started to map it but gave up. And the real catalyst here was the marking for “blue boiler” which was NOT connected to the blue boiler. My hair (not pictured) was torn out and on floor. The breaker for that boiler was not even in this panel.

Ok, so here is my nifty little circuit tracer device.

I plug the smaller piece into a receptacle and it sends a signal back to the breaker, and I can detect that signal with the wand portion, and that’s how I can trace the breaker for that circuit.

I plug the smaller piece into a receptacle and it sends a signal back to the breaker, and I can detect that signal with the wand portion, and that’s how I can trace the breaker for that circuit.

Here you see the main panel with the cover removed.

As a panel evolves with new circuits added over time, the wires get all over the place and it gets harder to trace the signal so we have to remove the panel to get closer to the actual wire with the wand. Note DO NOT remove your panel cover unless you know what you are doing!!! Last thing I need is a fricasseed blog reader!!!

As a panel evolves with new circuits added over time, the wires get all over the place and it gets harder to trace the signal so we have to remove the panel to get closer to the actual wire with the wand. Note DO NOT remove your panel cover unless you know what you are doing!!! Last thing I need is a fricasseed blog reader!!!

We were only tracing the basement circuits, so I would someday be able to kill power to items like boilers and hot water heaters in emergencies. I took some label stock and wrote down notes to stick on the panel. Sloppy, but way better than what I had.

So next, while I will no doubt get chastised by electricians, I also know a “usability expert” (these are people who actually go to college to learn how to make things easier to use) and no doubt I will be hearing from her about what I am doing wrong BUT my plan here is not just to label this one panel, but to label all three panels in the basement, and THEN I plan to post signage on all the basement devices like water heaters etc. to say “power shutoff: Panel A breaker 18″ So even a new service guy will have minimal trouble shutting stuff off as needed. And of course the panels themselves will be named and labeled A, B, and C. And of course I also have to post a legend of where is apt 1, which unit is apt 2, and so one. This was much more brainwork than I thought it would be!!

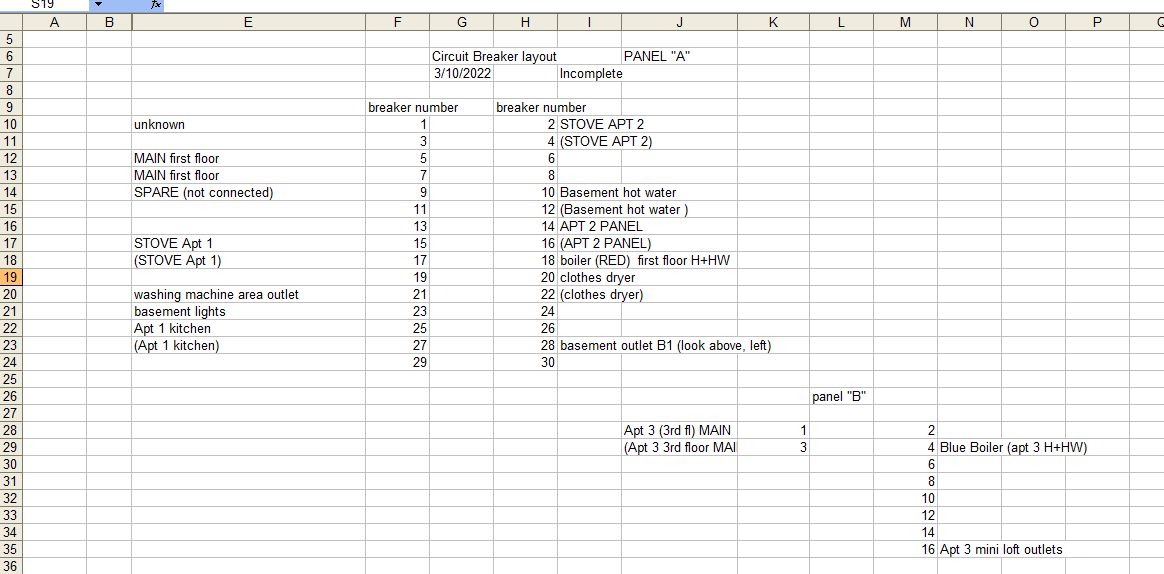

So this was the first draft: Hang on, more to come

I also posted a printed guide on the insides of the panel door:

And a few days later I printed up some better labels on crack & peel adhesive stock and finally got them in.

Again, it’s not done, and I am still refining my technique, but the key items in the basement (water heaters, boilers, etc.) are finally mapped to their breakers, and someday we will do the rest of the house!

–jl