Do you remember when you were a kid, playing some sort of improvised back yard version of baseball? Before the game started, everyone had to have a discussion of what was in bounds was out of bounds. The apple tree was first base, an old shoe was second base, and on it went. Once all of those basic guidelines were established, the game could begin in earnest.

We often think of athletic team coaches or symphony conductors as the epitome of management, but to me, that is a lesser level of management. The real managers of any situation are the people who, like those kids in the back yard, determine the basic rules for everyone to play by.

To give an example of this level of management in the realm of professional sports, in the NFL, they have what is known as the “Rules Committee.” These folks get together once a year and decide what the rules of the game shall be. “You must do this on each play, you cannot do this on any play, this is out of bounds,” and so on. They change various rules every year, for the purposes of making the game more exciting, safer for the players, etc.

There are, of course, other levels of managers in the sports world, ones that are much more visible.

You have coaches, who come up with strategies to make best use of resources within the framework of the game; that’s one kind of manager.

You have quarterbacks, who have to implement those strategies and occasionally improvise on the spot; that is another kind of manager.

Then you have the referees, who keep precise track of the clock and tell you when you’re doing things wrong; that’s yet another kind of manager.

And then you have cheerleaders, who generally just exhort excitement and maximum effort, that is yet another kind of manager.

In the symphonic world, conductors are seen as the epitome of management in action, but again, they aren’t the real managers. The real manager in a symphony concert is . . . the composer.

Like the NFL rules committee, composers lay out every single thing that the musicians are to do. It’s very precise, and playing anything else is clearly seen as being out of bounds. Even then, there is huge leeway in terms of how the players, as coaches, quarterbacks and defensive ends, can “play” within that very precise framework. And the better the job the composer did of laying out the framework, the more fun everyone has.

Conductors, alas, are really in the realm of head coach, referee, and cheerleader. Important roles, certainly, but nowhere near what the composer does. If you don’t believe me, go to a symphony concert and take note of how often any of the players take their eyes off the sheet music to look at the conductor. It happens, but only occasionally– mostly to know when to start and when to stop.

So my question to you, dear reader, is, what level of manager are you? Do you lay down very clear rules that everyone can understand, do you clearly define the object of the game, do you define the boundaries, and then do you step back and let everyone play to the best of their abilities?

Or are you skipping that step, and instead just sending in all the plays yourself, cheering from the sidelines, and constantly changing the rules ?

If the rules are not clear, or if they are constantly violated by you, well, it’s fun for a while. But eventually there are cries of foul and no fair, everyone takes their spirit of play and goes home. Structure equals safety and freedom. Without it, it’s just not fun anymore.

The same things that make backyard baseball fun– which include specific, collectively agreed-to rules, and the fair enforcement of same– are what make any work situation fun as well.

As I look back on it, three of the most successful and fun conductors I played for – Leonard Bernstein, John Williams, and Henry Mancini– were all composers. Why am I not surprised.

In your managing, I urge you to be a composer. Make clear rules and step back and let everyone else play. The real control is in the rules committee, not on each individual play. Anything else is out of bounds, and no fair.

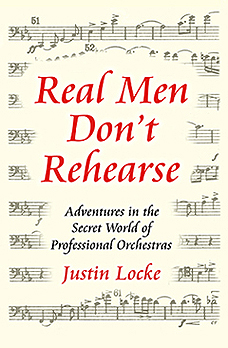

© Justin Locke

2 Responses to Do You Manage like a Conductor or like a Composer?